At the end of the summer back in 1997, I found myself suddenly and unexpectedly single. Sleeping on a sofa and driving an F Registration Sierra Sapphire 1.6 that was slow, smelly and very smoky.

Had I blacked out at the car auctions? Were the chips drugged? Who knows? But boy, did that car use oil. I could barely drive a 12-mile route to work without it needing a top up. It honestly cost me more in oil than petrol.

I have always associated since that burning oil is bad. The thing is this car was burning oil because it was knackered, however, in a healthy engine it can actually be beneficial.

Later that year I purchased a new car, a 2.0 5-cylinder turbo engine which at that moment was the fastest front wheel drive production car in the world. The engine was designed to use 1 litre of oil per 1000 miles.

This is classed as “normal usage” in the manual. 100,000 miles and 20 years later it is still producing 227bhp and running better than ever. So there are benefits.

What is the argument?

In Formula 1 burning oil as part of combustion is banned because of these perceived benefits, but it is claimed some teams have found a way to circumnavigate the rules.

Red Bull was the first to blow a whistle and point to Mercedes accusing them of using this method to get a power boost over the rest of the pack, specifically in the closing stages of qualifying or when they needed an extra little boost on the final laps last year. Mercedes shook their heads in amazement and it is believed that this year has pointed to Ferrari. The Italians naturally have denied it and have accredited their gains to mapping… which may be true.

In recent weeks the FIA have been looking into the situation and have reiterated the rules to all teams, although many pundits believe that the reminder was more for Ferraris benefit than anyone else.

This week Renault’s F1 engine chief Remi Taffin has suggested that there is no smoke without fire (excuse the pun), and simply the length of time the authority have spent on it shows they have a reason for suspicion or the speculation would have died down by now.

F1 engines and new ignition systems

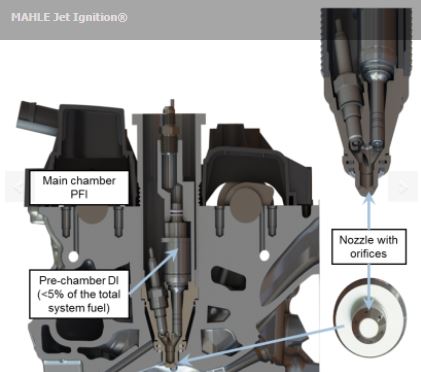

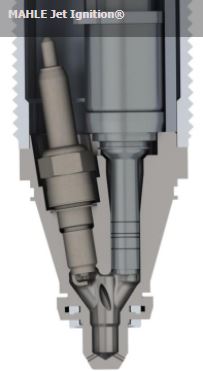

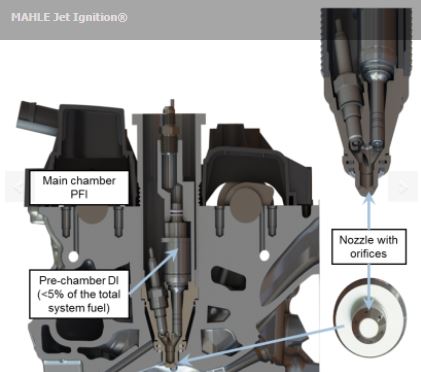

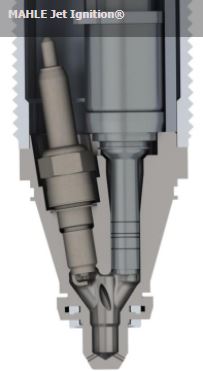

Mahle Jet Ignition. So the latest variants of F1 engines are not quite as simple as you might think. Yes, there is a spark plug, but that is to ignite a small amount of a rich mixture of fuel vapour in a small chamber at the top of the main cylinder. When combusted about five bolts of lightning travel through small holes at the bottom of the nozzle. This is then used to ignite the leaner mix in the main cylinder far more effectively. A tradition spark plug alone is far less effective.

These lightning bolts effectively cause chaos in the cylinder and cause more droplets of fuel to be burnt (at the same time from the outside in), in one big bang than anything has before. Result? More power from less fuel and that is everything in an engine that needs as much power as possible from a regulated fuel flow from a limited supply.

This is tricky to manage. It requires huge amounts of mapping data. Instructions from the ECU that dictates that when Air is x and fuel is y, and crank position is z then ignite at a. The issue comes when you’re running at 15,000 RPM. If the charge is released too early then the explosion that is supposed to push the piston back down might go off at the wrong time and cause “knock” and the sound of a misfire while the ECU franticly tries to compensate from its lookup tables. The point is that conditions vary wildly from track to track and minute to minute with air pressure, temperature etc.

Get this mapping right and its great – ask Mercedes. Get it wrong engines and gearboxes die – ask Honda, Getting the mapping right takes many hours track trial an error. Mercedes had this luxury, Honda didn’t. You can’t replicate real track conditions on any dyno, and track testing is heavily limited.

As a bandage (and further aid) there are many additives that you could use in fuel that help stabilise this process. The best solution is to use additives that make sure the fuel droplets are all the same size and go pop at the same time. This is maximising volumetric efficiency.

Volumetric Efficiency

This is simple. The cylinder is only so big. The trick is to get as much air and fuel in as you can but in a way that most of it can be converted to energy. Too much and it chokes, too little and your losing power. There is a curved line and you aim for the top. Most power from least fuel. If you stabilise the fuel through additives, you delay the combustion enough so everything goes bang when you want it to. They can also artificially increase the effective octane rating of the fuel. The FIA do not like this either.

What gains can be anticipated by such additives?

This can be itemised relatively quickly with a few bullet points

Enlarged capacity (effective) by being able to efficiently produce more power from less fuel, you are effectively replicating a bigger (standard) engine.

Volumetric efficiency, you could create the same power with less fuel when needed

Stabilised control, would give you less “knock” and more reliable and smooth power through improved combustion.

Unfortunately for the teams, fuel is heavily regulated and most of the polymers that can effect these benefits are banned.

Fuel Regulation

Fuel blends are very heavily guarded and regulated. The rules also change as teams with clever boffins in dark rooms find ways of “entering into the spirit” of the FIA law. Regulations have also changed on fuel for 2018 (most notably diolefins that likely reduce combustion temperature and so be more predictable)

These additives ARE however in the Oil the cars use.

Oil is far less regulated. Simple. 99% of the composition is very similar to the product you can buy on the shelves. Its that 1% that makes all the difference and closely guarded. However, going back to that 99%… Guess what.? Most of the major players in automotive lubricants worldwide like BP Castrol, Shell, Elf Auto, BPCL, HPCL, IOCL, Lubrizol, Infineum, EXXON rely mostly on such polymers because of how they serve “the consistency in quality.”

So all we have to do is find a way of letting a tiny percentage through into the cylinders. Government documents state clearly the benefit can be seen when these polymers account for as little as .001% of the combustible material. But…

Burning Oil is not allowed

The FIA regulations tells us this.

How might we get passed this?

(Without ending up with a horse’s head in my bed)

Actually on a turbo engine, it’s not that hard and could easily be designed into its specification. The easiest way (not that I am making any accusations) is to have a “controlled” leaky turbo bearing on the compressor side. Shafts have bearings and shafts that need to be cooled. Engine oil is used to cool it. If they are a bit “leaky” (not in a Ford Sierra way) then oil ends up in the plenum as a mist, which continues into the cylinders.

If say in “Qualy Mode” the mapping allowed spikes of boost and increased oil pressures (sensors also changed for next year and have to meet FIA criteria), then there is a chance that some might get through… The FIA have to allow for SOME “incidental leakage” It makes it very hard to govern.

Obviously we should not too much oil to get through, and of course not all the while (perhaps when you need an extra squirt at the end of qualifying 3 or last few laps of the race?), or else when the lubricant gets inspected after the race it might have used a bit too much to be “incidental”.

But we don’t need much of these polymers to make a difference. Oh did I explain that such things can also clean up smoke products, and only eject carbon dioxide and water as by products?

Why have the FIA been so soft in its investigations?

Plausible deniability. Teams such as Torro Rosso and Force India are supplied complete power units from the manufacturer. Accusations aimed at works teams date back to last year. Evidence erased. This year’s data could probably be argued by expensive lawyers to be “incidental”

Sahara Force India’s COO Otmar Szarfnauer, who run Mercedes customer engines, told Autosport that he regrets the oil burn matter has dragged on for so long. He said: “The FIA had an opportunity to fix it a long time ago and didn’t take it. It is one of those things – my neighbour once told me if you put your time in early with your child, once they are an adult you are done.”

Even so, assume you could prove it, how would you quantify the gains and what penalties would be made? Would you punish the manufacturer or the purchasing team, or both? Stripping titles, changing positions. There would be huge and complicated legal and financial implications when dealing with this in retrospect.

Easiest thing is to change the regulations for next year and reiterate the regulations to all teams this year. Which is what they did on 23rd June when the FIA sent a reminder to teams ahead of the Azerbaijan Grand Prix about potentially burning oil to provide a pace boost, especially in qualifying.

If I was a team principle, I might decide to avoid any further unwanted FIA investigations or penalties and launch a preemptive strike. I might wait until we are starting to focus on next year’s engine and reluctantly retire my engine designer as a sacrifice to the gods and look at some fresh meat with fresh ideas based on new regulations for 2018.

Or am I getting too sceptical in my old age?

By Steve Barby

Mahle Jet Ignition. So the latest variants of F1 engines are not quite as simple as you might think. Yes, there is a spark plug, but that is to ignite a small amount of a rich mixture of fuel vapour in a small chamber at the top of the main cylinder. When combusted about five bolts of lightning travel through small holes at the bottom of the nozzle. This is then used to ignite the leaner mix in the main cylinder far more effectively. A tradition spark plug alone is far less effective.

Mahle Jet Ignition. So the latest variants of F1 engines are not quite as simple as you might think. Yes, there is a spark plug, but that is to ignite a small amount of a rich mixture of fuel vapour in a small chamber at the top of the main cylinder. When combusted about five bolts of lightning travel through small holes at the bottom of the nozzle. This is then used to ignite the leaner mix in the main cylinder far more effectively. A tradition spark plug alone is far less effective.